The travails of the rookie filmmaker

How many mistakes can one guy make in three weeks on the road? Let us count.

This is the debut post in my Last Great Documentary series. I’ll be chronicling my journey to make a documentary about the so-called “last great newspaper war” in Anchorage, AK. I’ve been researching the project for 18 months and have recently begun on-camera interviews. The subjects of the film are journalists who have scattered across the country in the decades since the war’s conclusion in 1992.

So there I was, sitting in my car in the driveway, trying to get my mind right. I’d just wedged three bags of video gear, three softboxes, a duffle of clothes, a 13-year-old dog, and an oversized dog bed into my Honda Pilot. I put the key into the ignition and paused for a good long moment. “I think we’re ready,” I muttered, ostensibly to my dog. But I probably just needed to say it out loud. Saying is believing, right?

Thanks for reading Talking Documentary! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

But was I actually ready? Not completely, as it turns out.

I was about to depart on a 19-day, 5,000-mile documentary trip that would take me from my home in Durham, NC, all the way to Durango, CO, by way of Minneapolis to the north and Santa Fe to the south. I had scheduled seven interviews in seven locations. If anything were to go wrong—say, my 17-year-old car spitting the bit, or my dog (who has adrenal cancer) having a medical emergency—weeks of careful planning could go up in smoke.

I should mention here: I’m a solo filmmaker. Also, sort of a fledgling one.

To be fair, I’m no stranger to cameras, interviewing, or writing. I started out as a newspaper reporter. I know how to dig around, formulate questions, and play dumb to get an interviewee to open up. I also ran a freelance video production business for a few years. So I’m not without skills.

But a full-fledged documentary project is a different beast. And one I’ve been preparing myself to undertake for several years now.

How does a middle-aged career refugee learn to make a documentary film? Well, not NYU film school, that’s for sure. Who’s got the time and money for that? Happily, in 2023, there are so many ways to learn filmmaking, many of them free, and many of them good. My recipe: a steady diet of YouTube videos and a side order of talking to experienced filmmakers on the Talking Documentary podcast. (Oh, and a pandemic void that screamed to be filled … by anything.)

It’s not NYU film school, but it works. And the price is right.

But it’s time to stop learning and start doing. To take my shots and take my licks. And, hoo boy, did I ever take a few licks on this trip. I committed at least one painful mistake in all seven of my interviews. Was it painful? Oh, hell yes. But there’s no learning like painful learning.

Let’s switch into present tense, hit the road, and revisit some of my follies.

Day 3: Chicago, IL - I get things going on a cold, gray morning on the outskirts of Chicago. I’m interviewing Dave in my room at the Comfort Suites. The hotel is a mixed blessing. The upside: I got to set up the night before. The downside: the hotel walls might as well be sheets held up by clothespins. I had set the interview for 9:30 a.m., hoping we’d find the quiet spot between guests departing and maids spinning into action. It’s a cute plan that fails completely. Turns out I’m on the same floor with a pack of jubilant teens who have nothing better to do than walk up and down the hallway. Over and over. I stop Dave mid-sentence every time this happens. At one point Dave suggests putting a towel at the base of the door. I ask him if he wants to join me on the road. I need a first A.D. Dave declines. The towel helps. We muddle through.

What I learned: Conduct hotel interviews in the early afternoon, and also … do better research on the hotel. The Comfort Suites where I shot this interview had faux wood floors (it was a pet-friendly room). The sound is harsh and reverberant. Good thing I brought moving blankets.

Day 5: Mora, MN - The drive across Wisconsin is relentlessly cold, gray, and windy. I’m reminded that in the upper Midwest, April doesn’t mean what you think it means. My next interviewee, Tom, lives in a cabin deep in the Minnesota woods. It has snowed recently. A lot. Tom’s driveway is blocked by plowed snow, so we’re forced to posthole my gear 75 yards through knee-high drifts (looking very much like Steve Buscemi burying the suitcase of cash in Fargo). The interview setup goes relatively well, though I have to avoid all windows in my shot (my Amaran 200x can’t overcome the intense light bouncing off the blanket of snow). I settle for an imperfect backdrop of wood paneling and an abstract painting of orange trees. But this is a documentary, not Lawrence of Arabia. It’ll do. But disaster strikes halfway through the interview. I note with horror that my C70 is no longer recording. The SD card I thought was formatted is in fact … not. I lose 12 minutes of the interview. I mumble to Tom that we have a small problem, but I find another card and keep things moving. I’m crying inside but I remain outwardly chipper. As I learned from filmmaker Bryce NcNabb, my No. 1 priority is keeping the interviewee relaxed and engaged (or at least the top priority after removing the lens cap).

What I learned: Don’t trust your recall. Trust your eyes. Create a pre-roll checklist that you run before every interview. I’m going to check the top left-hand corner of my monitor before each interview (if it doesn’t say 131 minutes of run-time, something is wrong).

Day 6: Minneapolis, MN - One fun aspect of this trip is sizing up random spaces and figuring out where the interview will happen. This process has to happen quickly because, as a solo filmmaker, I’m responsible for getting everything in place: sound treatment, multi-point lighting, framing and composition, double-system sound, and on and on. There isn’t time to try multiple setups. You make your assessment and get going. Today’s interview with Gail takes place in a tiny house near downtown that she rents on Airbnb. I set up swiftly—this is my third interview, and I’m starting to find my rhythm. The interview proceeds smoothly for the most part, but we’re along the flight path into Minneapolis−Saint Paul International Airport, so we’re forced to pause frequently. But that’s the gremlin I know. The gremlin I don’t? When I review the footage afterward, I note several instances where the image vibrates. Gail was a bit fidgety and sporadically bounced her right knee. I noted this in real time. What I didn’t note was the spongy floorboard beneath the tripod. When Gail’s knee bounced, so did the camera. Egad.

What I learned: Travel tripods are marvels of technology (my carbon-fiber model weighs only a few pounds and collapses to 20 inches). But lightweight can be a liability. For all its virtues, feather-light gear is vulnerable to its environment. Of course, most tripods feature a hook beneath the fluid head. Hang the sandbag there, stupid.

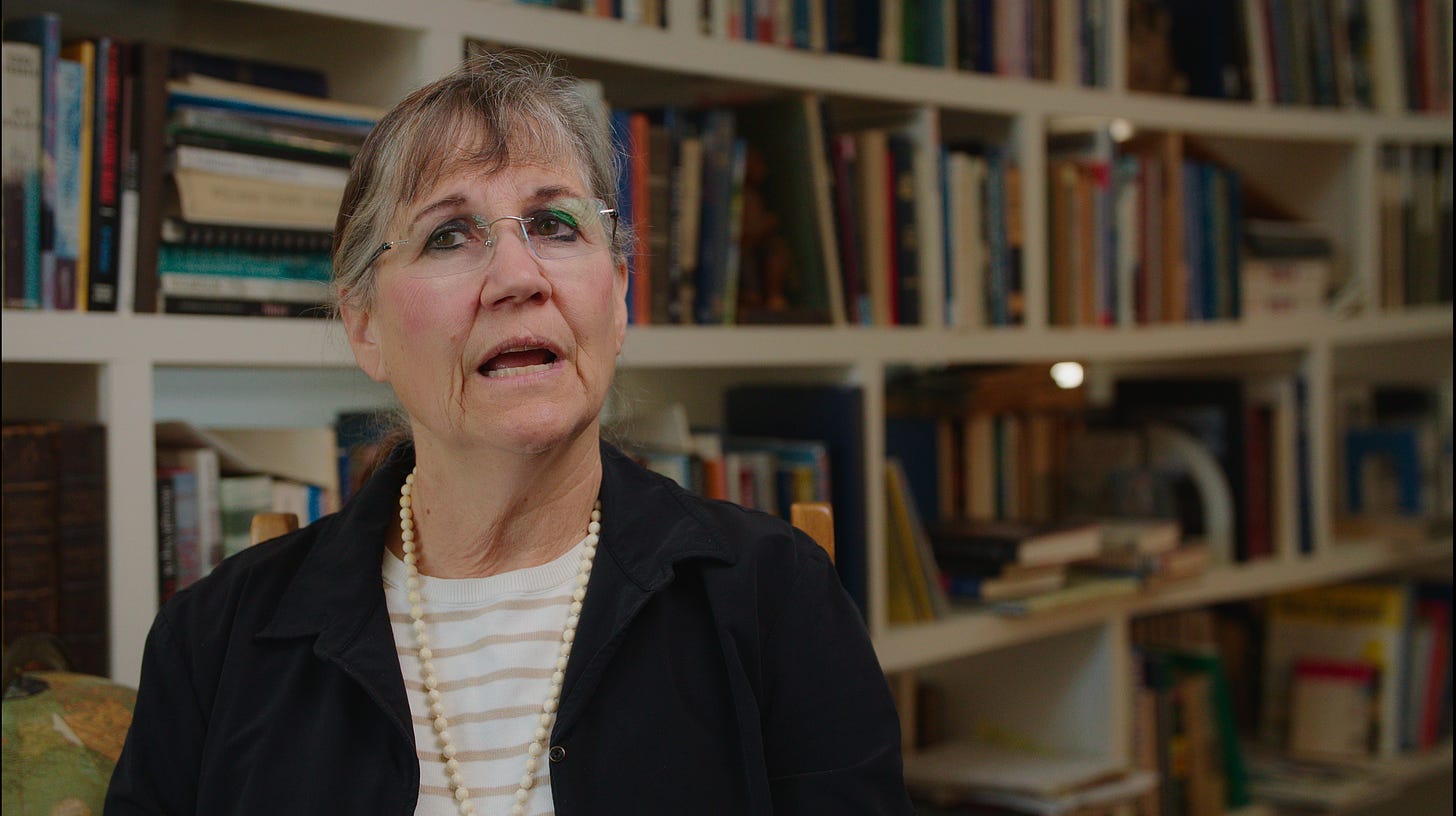

Day 8: Orchard, NE. More rain and wind across Iowa. My diet is deteriorating on the road, and I go looking for green powder in Sioux City. I’d have had better odds of finding a subway train. But the sun is shining when I arrive at AJ’s farm in the northeastern corner of Nebraska. AJ is not only my interviewee, she is my host as well—and a talented one at that. She plies me with an array of homemade treats. Life is good. The interview promises to be a good one as well. I feel relaxed and less rushed, and I choose a shot against a bookshelf that features interesting lines. But it’s a tight space, and I’m forced to position myself behind the camera (where normally I’m astride it). This forces me to lean slightly to make eye contact with AJ. And in turn, AJ does what humans tend to do: she mirrors my body language. I adjust her several times during the interview, but we continue to struggle with the setup. Also, AJ’s eyeglasses betray the presence of a distant window as well as the egg crate diffusion on my key light. Ugh.

What I learned: Slow down, Scotty! Take care of the basics! If your interviewee is wearing glasses and there’s a window behind the camera, you must cover it. Full stop. Duvetyne and clamps are our friends. Also, if you don’t have enough space for you and the interviewee to sit naturally, find a different setup. What feels awkward in real life can look even more awkward on camera. The viewer will know something isn’t right even if they can’t put a finger on it.

Day 13: Durango, CO. Somewhere around the Nebraska-Colorado border, I cross back into spring again. The sun returns to the sky and the winds subside. I skirt the Rocky Mountains to the south and arrive in Durango just before sundown. Durango is probably the toniest, grass-fed mountain town you’ve never been to. Mike and I feast on burgers and ice cream sandwiches. It’s the meal of high achievers everywhere. I arise with gusto the next morning. It’s a brilliant, sunny day on Mike’s 17-acre ranch. There is no excuse for imperfection today. I’ve had a full day to explore the space I’ll be setting up in. Alas, fifteen minutes into the interview, I notice a tree lamp growing out of Mike’s head (he had moved the lamp slightly while getting to his chair). I reposition the lamp mid-interview, which creates a minor continuity issue. But that seems like the lesser sin here. At least Mike doesn’t wear glasses.

What I learned: Again, slow down! The talent agreed to sit for an interview, so they’re likely fine if you take an extra 5-10 minutes to ensure no lamps have gone for a walk. Both parties are invested in looking great. Take a deep breath and get it right.

Day 14: Santa Fe, NM. This is by far my trickiest shoot. Brad is squeezing me in between two business calls a few hours apart. I have 30-45 minutes to set up (and less than that to break down). There is no margin for error, so I immediately make one. I choose a setup that proves impossible (a chandelier hangs where the key light needs to be). Nothing to do but reverse the shot and rearrange the gear. Brad reappears ahead of schedule. He’s making polite conversation and I’m trying to participate. But I’ve made mistakes even without distractions, so I have to focus right now. I keep adjusting the key and tripod, an inch here, a foot there, muttering as I go. I cannot get the shot I want. Brad is also a filmmaker. He encourages me not to rush, but I feel the pressure anyway. I don’t like my shot and I don’t know how to fix it—not quickly, at least. I’m rushing, which flusters me, and that in turn slows down my thinking. Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast … as the saying goes. I’m moving fast and bumpy and getting nowhere fast. I finally decide good enough is good enough. Not surprisingly, a few minutes into the interview, I notice yet another problem in the background. Two straight days, two straight lamps in a bad spot. I also notice afterward that Brad has deep-set eyes. I needed to lower the key to properly illuminate them. Sigh.

What I learned: For the love of god, slow down! Better to run out of time than have the entire interview compromised. As for my struggles with run-and-gun composition, I suppose I’ll just have to improve through time and experience. Thankfully, Brad was an amazing interview and will make up for my shortcomings.

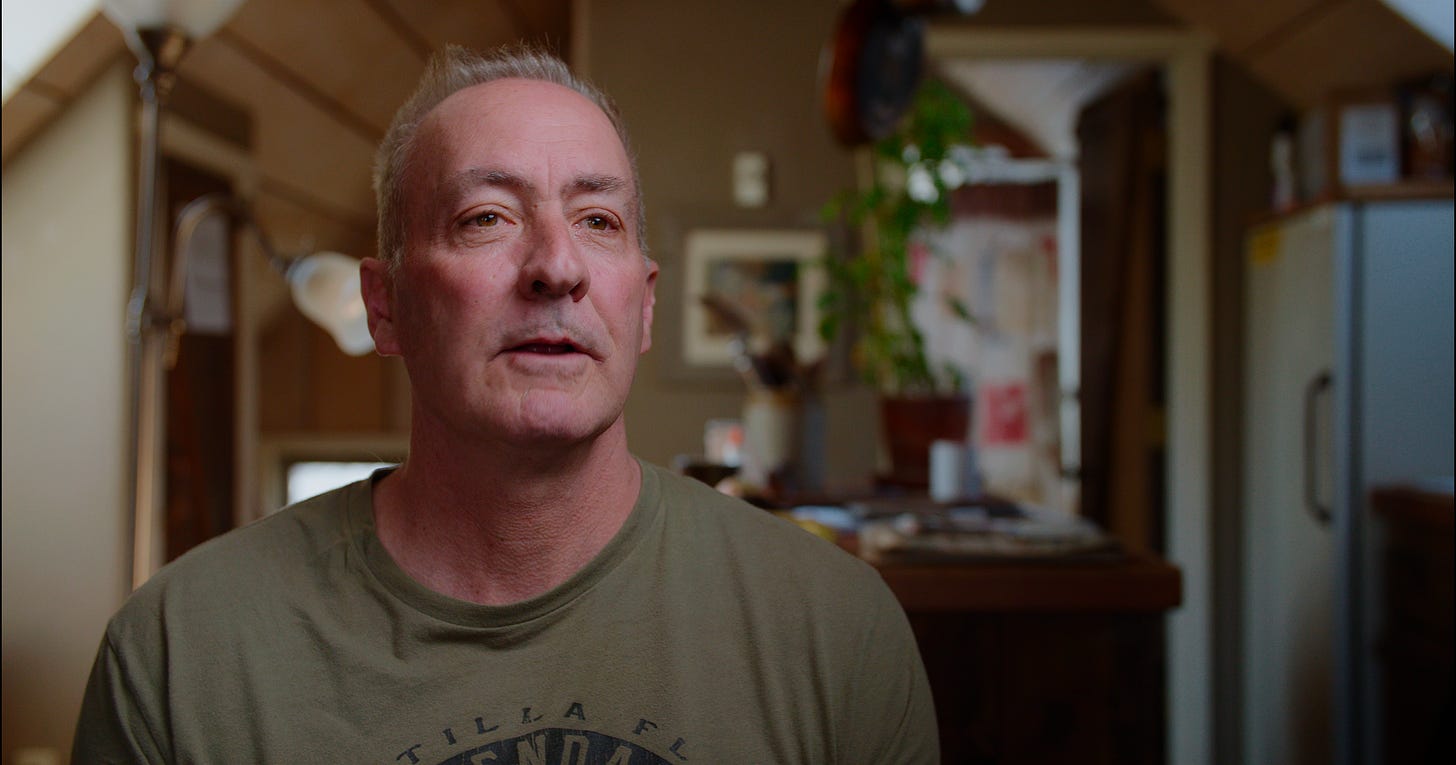

Day 17: Murphysboro, IL. I’m now in the home stretch. I rip across New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri in two days. I haven’t stepped on a scale in three weeks, but my knees tell me I’ve gained five pounds. I should wake up early and go for a run. Instead, Mark and I go downtown to Faye’s, where we dispatch homemade biscuits and gravy and a pretty pink cruller (only three days to go, might as well lean into my decay). As in Durango, I have a full day to explore my interview space and plenty of time to set up. But either out of fatigue or complacency, I don’t fully capitalize on this. First, I choose to shoot against a fireplace, which doesn’t provide much color contrast. I also overlook a reflection on the metallic fireplace thingy (what do you call that?). Perhaps I saw it and got distracted. Regardless, as the interview proceeds, I keep seeing that hot spot in the monitor and it bothers me. I pause the interview so I can identify the source and fix it. The other issue I run into: Mark is a passionate guy and quite demonstrative at times. He gets so excited that his arms and legs rattle into the stand that holds the key light. I reposition it further away but wonder if this will introduce a continuity issue.

What I learned: No excuse for that hot spot. I continue to optimize for the interviewee’s experience, which leads me to conclude, “This is good enough … let’s not keep them waiting.” I’m not exercising the artist’s prerogative to get everything “just so” and my images are suffering for it. I need to develop more confidence and start only when I’m ready—not a second sooner. I’ll bet Picasso never rushed. As for the gesticulating interviewee, well, that’s just one of those things. I’m traveling with a smaller softbox (25 inches) for logistical reasons, so it’s doubly important I position the key light just out of frame (close light is soft light, after all).

Epilogue: After my final interview, I still had 700 miles of driving to get home. Plenty of miles to reflect on the whirlwind of the previous three weeks. It went by impossibly fast. Time moves swiftly when the brain is constantly at work, in this case processing the logistical demands of moving a small filmmaking operation (and a senior dog) into and out of 16 spaces in 18 days.

Still, I have to get better at slowing and quieting my mind. Filmmaking is as much a mental game as a physical one. Fatigue is a factor as well. Three weeks is a long time to stay sharp when you’re living out of a car and choking down Subway sandwiches in random parking lots.

My next documentary trip will take me up the California coast as I interview more veterans of the last great newspaper war. That trip will involve plane travel. That will be a whole new realm of logistics to learn about.

How did this trip sharpen me as a filmmaker? Too early to know. I can only trust that it did. Making documentaries is like anything else in this life: a journey toward the unknown, undertaken with hope.-30-

Fight the good fight. As a one man band, you gotta give a lot of grace. I feel that pain.

great story, I can totally relate